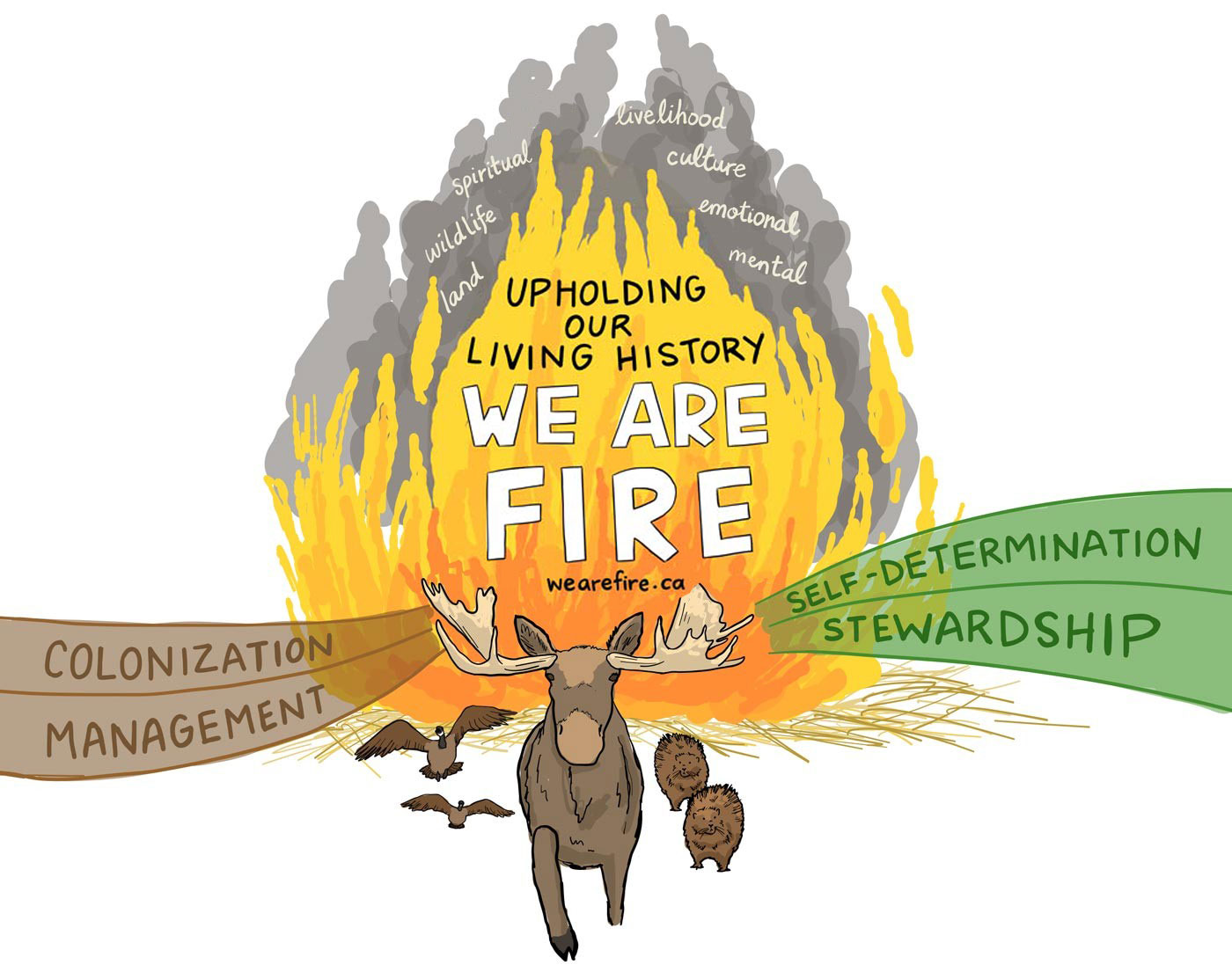

Our Living Fire History

I saw a blank canvas. From there, I saw a Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women (MMIW) survivor. She survived the fire of residential school. I just saw it (on the blank canvas). Fire burning the negativity away towards a good new start.

Illustration courtesy Lexie Shaw.

Content Warning

INFORMATION PRESENTED IN THIS SECTION OF THE WE ARE FIRE TOOLKIT CONTAINS CONTENT WHICH MAY BE SENSITIVE, TRIGGERING OR DIFFICULT TO DEAL WITH EMOTIONALLY.

If you experience any of these responses, we encourage you to contact a mental health specialist or counsellor, your local Elder or Knowledge Carrier or other support person.

You can also consult

It is not our intention to cause any harm or discomfort.

Rather, we want to share the extent of the living history of Canada and how specific events, policies, laws and practices impact the lives, rights, governance systems and lands of Indigenous Peoples and their communities over the generations.

Every landscape reflects the history and culture of the people who inhabit it. The worldview of a society is often written more truthfully on the land than in its documents.[1]

Fire, Law and Politics: A Timeline

To understand and appreciate our living history with fire on the land, it is important to know how politics, specific laws and policies have historically affected Indigenous Peoples and uses of fire in Canada.

We need to understand how specific case law, policies, legislation and practices recognize and reconcile the effects of colonization which includes uses of fire and Indigenous Peoples’ title and inherent rights to lands across Canada.

Pre-Confederation (Before 1867—an overview)

Before Confederation in Canada, Indigenous Ecological Knowledge embraced Indigenous-led fire practices to support land stewardship.

Many Indigenous Peoples and communities were skilled in applying fire on the land.

Uses of fire for land management were selectively and cautiously applied with specific objectives—for example, improving production of food and medicinal plants; clearing trails; improving forage production for wildlife and driving game animals; and fostering relationships in community, including with the land.

Royal Proclamation of 1763

As settlers occupied British North America, the British government proclaimed that the interests of Aboriginal People and their lands must be protected under the Crown.

For example, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 describes that the Crown is required to have an agreement in place to acquire land from Aboriginal People. To date, this proclamation has been and continues to be significant in terms of recognizing Aboriginal title and rights.

1849—Depopulation of Indigenous Peoples

In about 1849, there was a significant depopulation of Indigenous Peoples due to epidemics of European diseases, for example, smallpox, influenza and measles.

Confederation (1867 to present)

Constitution Act, 1867 – Section 91(24)

This specific section of the Act says that the Government of Canada has exclusive legislative authority for Indians and lands reserved for Indians, called reservations.

Residential School System in Canada (1830s to 1990s)

From the 1830s to the 1990s, Indigenous children and youth throughout Canada were forcibly removed from their families and cultures and sent to residential schools.

The residential school system was funded by the Government of Canada and administered by Christian churches.

The residential school system took over 150,000 Indigenous children from their families and communities to non-Indigenous operated residential schools across Canada. This system was intended to isolate Indigenous children by removing them from their languages, families, communities and cultures—thereby assimilating them into non-Indigenous Canadian culture.

There were approximately 139 residential schools across Canada.

In addition to the negative effects of legislated assimilation, there were allegations that many Indigenous children suffered psychological, physical and sexual abuse; overcrowding; lack of medical care and poor sanitation during their attendance at residential school.

Thousands of court cases filed by residential school survivors and their families against the Government of Canada led to the largest class-action lawsuit in Canadian history and the subsequent establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

As a result of intergenerational trauma from the residential school system, wisdom about Indigenous-led fire practices was lost or remained hidden.

Indian Act (1876 to present)

This law, first passed in 1876, gave the Government of Canada exclusive authority over Indian People living on reserves. The Act defines who are Indians and their associated rights.

The Act previously denied First Nations People of sovereignty and self-determination.

Another impact of the Indian Act was the pass system where Indian People living on reserves could not travel outside of their reserves without approval. The pass system led to a further disconnect of First Nations People from the land.

The Act previously denied First Nations People the right to vote unless they gave up their Indian status and associated rights.

In 1960, First Nations People received the right to vote in federal elections without giving up their Indian status.

At present, the Indian Act remains in effect. Though amendments were made to the statute from approximately 1881 to 2000, the Act remains fundamentally unchanged since 1876. An amendment in 2000 allows First Nations band members living off reserve to vote in band elections and referendums.

The Indian Act is currently administered by the federal Minister Responsible for Indigenous-Crown Relations.

Saskatchewan joins Canada (1905)

On September 1, 1905, Saskatchewan joined Canada and adopted the Saskatchewan Act, thereby entering into Confederation.

Fire suppression policies (early 1900s)

In the early 1900s, fire suppression policies were widely enacted and enforced in Canada.

During this time, Indigenous Peoples were required by law to fight wildfires near their homes or be fined or jailed.

In Canada, all forms of burning were outlawed and replaced with a centralized system that aimed to suppress all forest fires to initially protect watersheds and timber values.

These policies restricted the frequency, seasonality, extent and magnitude of Indigenous-led fire practices.

Indigenous-led fire practices were hidden, but never at the scale they had been pre-Confederation.

In Saskatchewan, burning was first regulated in the province in the late 1800s/early 1900s via The Prairie and Forest Fire Ordinance.[2]

Fire use by Euro-Canadian settlers in northern Saskatchewan (early 1900s)

In the early 1900s, Euro-Canadian settlers used fires in their gradual move into northern Saskatchewan—clearing what was intended to be agricultural homeland.

Euro-Canadians burned agriculture for different reasons: to promote monoculture and to turn land into private property to be owned and managed by settlers.

However, these set fires often got out of hand because newcomers did not understand fire behaviour.

For example, in 1908, a vast area north of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan was burned when set fires burned out of control and spread into nearby parkland and forest. The blaze destroyed several farmhouses, over 50 tons of hay and hundreds of cords of cut wood.

The frequency and size of forest fires increased with the influx of Euro-Canadian newcomers to northern Saskatchewan.

Jurisdiction for wildfire response in Saskatchewan (1930)

In 1930, via the Natural Resource Transfer Act, the Government of Saskatchewan took over wildfire response and responsibilities from the Government of Canada, along with other natural resource responsibilities and royalties.

The Government of Saskatchewan had greater incentive to protect forestry interests than the federal government previously had, so they increased fire suppression practices.

The 1930s coincided with a massive settler migration northwards to the boreal region as the province incentivized settlers to engage in a mixed forestry-agriculture economy.

Settlers hoped that forestry could offset some economic hardships facing them during the Great Depression. Forestry resulted in a huge influx of fires throughout the fringe. A big investment in suppression infrastructure developed as a response to these fires.

The Natural Resource Transfer Act was approved without Indigenous consultation. Strongly contested in some Indigenous communities, it has had a huge impact on Indigenous Peoples by imposing seasons, trapping blocks and other regulatory systems that impede Indigenous inherent rights.[3]

“Smokey Bear” and related government-led fire suppression education campaigns (circa 1944)

Around 1944, government-led education campaigns were rolled out to the public, for example, the “Smokey Bear” campaign on fire and smoke suppression.

The position of these public education campaigns is that fires in forests and surrounding areas are destructive and hazardous, so they need to be suppressed.

Report of the Saskatchewan Royal Commission on Forestry (1947)

In 1947, the Report of the Saskatchewan Royal Commission on Forestry was published.

The Commission provided an inventory of Saskatchewan forests and insights for developing Saskatchewan's forestry sector.

The Government of Saskatchewan sought to greatly increase their forestry outputs coinciding with a post-World War II housing and economic boom.

The Commission led to massive investments in fire suppression, including a major expansion and retrofitting of the tower lookout system.

Fires were believed to cause great harm to forestry potential in the province. Ninety percent of those fires were caused by humans.

Continuation of fire suppression policies (1940s to mid-1990s)

From the 1940s to the 1980s and from the 1980s to the mid-1990s, government legislation and policy directives focused on fire suppression, meaning the extinguishing of all fires. Forest and land management were based on commercial and related economic development values, particularly protecting timber.

For example, the boreal forest was divided into a primary response zone (full suppression) in areas of high commercial timber and a secondary response zone in “low value” commercial timber, roughly corresponding to the shield region above the Churchill River.

Over time, these directives significantly affected and influenced other land values, for example, socio-cultural and ecological values. They also affected the natural state of the forests and surrounding lands like meadows.

Indigenous firefighter recruitment and conscription (Saskatchewan)

In the late 1950s, the Province of Saskatchewan began recruiting and conscripting Indigenous firefighters and “depended heavily on them for manual labour on fire lines.”[4]

The Province of Saskatchewan opened “native fire schools” to train Indigenous firefighters and tower lookout personnel. Attendees of the schools included long-term Indigenous firefighters who had, in many instances, taught their instructors.

1969 White Paper

Former Minister of Indian Affairs Jean Chrétien prepared a policy document (1969 White Paper) that proposed the elimination of the Indian Act and Aboriginal land claims. The White Paper also supported the assimilation of First Nations People into the Canadian population as “other visible minorities” rather than being recognized as a distinct racial group.

Harold Cardinal and the Indian Chiefs of Alberta countered the White Paper by preparing the “Citizens Plus” policy document (Red Paper).

The Red Paper coupled with the Calder v. British Columbia (1973) decision were contributing factors for the Liberal Party of Canada, the governing party of Canada during this time, to step away from the policy recommendations described in the 1969 White Paper.

Wildland firefighting as a preferred employment for Indigenous Peoples (1970s – 1980s)

In the 1970s and 1980s, wildland firefighting was a preferred job for many Indigenous Peoples, where they could make money during the summer firefighting season with friends and relatives and then pursue cultural activities in the off-season.

In addition to becoming frontline firefighters, many Indigenous firefighters became part of specialized firefighting teams known as “Smokejumpers”—the first of their kind in Canada—where crews parachuted into remote areas, attacking fires before other recruits arrived on the ground.

Constitution Act, 1982 – Section 35

This specific section of the Act provides constitutional protection to the rights of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada.

Examples of Aboriginal rights that Section 35 has been found to protect are fishing, logging, hunting, Aboriginal title or the right to land and the right to enforcement of treaties.

Saskatchewan First Nation Forest Fire Protection Services Agreement (1992 to present)

In 1992, the Saskatchewan First Nation Forest Fire Protection Services Agreement was signed, making the Government of Saskatchewan the first province in the country to have an official agreement for forest fire protection with First Nations and the federal government. First Nations initiated this process to ensure their members had the training and ability to fight fires near and outside of their communities.

As of 2022, there are 83 five-person Type II crews: 61 First Nations crews and 22 Métis crews, most of whom were trained by Indigenous instructors contracted by the Prince Albert Grand Council. Many are third- or fourth-generation firefighters who are hired by the Government of Saskatchewan’s former Wildfire Management Branch.

Changes in wildland firefighter training policies (1990s to present)

The 1990s brought policy changes. Fitness tests were required, and firefighting became an option for many adrenaline seekers, including non-Indigenous post-secondary students who fought fires during their summer breaks.

In Canada, from the 1990s to present, the majority of Indigenous firefighters remain on entry-level crews, despite having years of practical hands-on experience and leadership in wildfire management.

R. v. Sparrow [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075 and R. v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507

The Aboriginal right to fish for food.[4]

This significant court case determined that there is, under the Canadian Constitution, an existing Aboriginal right to fish for food for social and ceremonial purposes. In 1984, the appellant Ronald Sparrow was charged under the Fisheries Act for fishing with a drift net longer than permitted by the terms laid out in the Band’s Indian food fishing license.[2] Sparrow admitted the facts alleged constituted an offence, but he defended himself based on the fact that he was exercising an existing Aboriginal right to fish and that the net length restriction contained in the Band’s licence was invalid or that it was inconsistent.

This was the first case for the Supreme Court of Canada to interpret what Section 35 actually meant.[3]

The Court ruled that the Constitution Act provides “a strong measure of protection” for Aboriginal rights, and that the proposed government regulations that infringe on the exercise of those rights must be constitutionally justified.[4]

Saskatchewan Forest Fire Policy Study (1995)

In the mid-1990s, the Province of Saskatchewan shifted toward a values-based approach.

The Saskatchewan Forest Fire Policy Study focused on developing a range of options for fire management and recommended the best option toward resolving the conflict between human activity and the natural role of fire.

This policy was to address costs of fire suppression, expected increases in commercial timber value and the natural role of fire in the forest.

Powley case (2003)

On September 19, 2003, the Supreme Court of Canada acknowledged the existence of Métis as a distinct Aboriginal People in Canada with existing rights that are protected by the Constitution Act, 1982 — Section 35.

Fire and Forest Insect and Disease Policy Framework (Government of Saskatchewan, 2003)

In 2003, the Fire and Forest Insect and Disease Management Policy Framework was approved, shifting policy toward a “values at risk” approach and recognizing the natural role of fire on the land.

Protection of human life and safety is the highest priority, followed by communities and major public infrastructure, commercial forest and then “other values.”

When fire protection resources are stretched, decisions between which other values to protect may need to be made.

Called by locals the “let it burn” policy, this directive allowed fires to burn until they encroach upon something designated of “value” (typically human life, community structures, public infrastructure and commercial timber).

Fire managers developed an integrated approach to prioritize the economic, social, cultural and ecological values based on how the public prioritizes these values.

This policy was fully consulted on with all stakeholders, all northern communities and Indigenous groups. There was also a public review completed in 2006 to reaffirm the priorities for this policy.

While wildfire managers, scientists and politicians advocated for policies of fire-reintegration as an ecologically sound and financially responsible way forward, many locals argued that this policy is a direct insult to Indigenous sovereignty, destroying contemporary forested lands and rebuilding them through state-sanctioned settler values.

For example, in northern Saskatchewan, Indigenous groups did not consent to this policy of not suppressing fire if provincial government-determined values were not at risk. Therefore, the Province of Saskatchewan’s decision-making authority of how Indigenous lands are impacted by fire is disputed.

As of 2022, the three major fire response areas in the Province of Saskatchewan are the Primary Timber Area (full suppression), Secondary Timber Area (full or partial suppression), and Area North of the Primary and Secondary Timber Area (values protection).

Canada Wildland Fire Strategy (2005)

Published in 2005 by the Canadian Council of Forest Ministers, the Canada Wildland Fire Strategy is a guiding document for wildfire agencies across the country.

The objectives of this Strategy emphasized resilient communities and an empowered public, healthy and productive forest ecosystems and modern business practices.

First Nations-Federal Crown Political Accord on the Recognition and Implementation of First Nations Governments (2005)

Signed in May 2005, this national agreement between First Nations and the Government of Canada focuses on the reconciliation, collaborative review and development of policies relating to First Nations’ rights and self-government.

Statement of Apology to former students of Indian Residential Schools (2008)

On June 11, 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper officially apologized on behalf of the Government of Canada for the Indian Residential School system.

In a move toward reconciliation between Indigenous Peoples, particularly former Residential School survivors and the Government of Canada, the statement of apology was intended to write a new chapter in Canadian history of working together in partnership to ensure that government systems and processes like Residential Schools will not be repeated for future generations.

On July 25, 2022 in Maskwacis, Alberta, Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church, formally apologized for the Catholic Church’s role in the Indian Residential School system.[9]

First Nations and Métis Consultation Policy Framework

The Saskatchewan Public Safety Agency (SPSA) must follow the First Nations and Métis Consultation Policy Framework.

As an example, for muskrat burns in the Saskatchewan River Delta, SPSA follows the above Framework and provides notification letters to First Nations and Métis communities in and around the Delta on behalf of the fur blocks.

Bill C-45 and the Idle No More Movement (2012)

On October 18, 2012, The Government of Canada introduced Bill C-45: A Second Act to Implement Certain Provisions of the Budget Tabled in Parliament on March 29, 2012, and Other Measures.

Bill C-45 was an omnibus budget bill that changed legislation contained in over 60 acts or regulations.

Changes to legislation included the Indian Act, Navigation Protection Act (former Navigable Waters Protection Act) and Environmental Assessment Act, and these changes served as a catalyst for the Idle No More Movement in the fall of 2012.

The Idle No More Movement saw Indigenous Peoples from across Canada at the grassroots level gather in solidarity through rallies and social media (on Twitter at #IdleNoMore) raising awareness about Indigenous issues in response to Bill C-45.

Organizers and supporters of The Idle No More Movement viewed Bill C-45 as an erosion of treaty and Aboriginal rights and its introduction demonstrated a lack of consultation with Indigenous Peoples on changes to federal legislation.

On December 10, 2012, a National Day of Solidarity and Resurgence was held.

Despite the actions of the Idle No More Movement, Bill C-45 was passed and received royal assent on December 14, 2012.

Bill C-45 is now referred to as the Jobs and Growth Act, 2012.

Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, 2014 SCC 44

First declaration of Aboriginal title.[10]

This significant court decision was the first time any Canadian court declared Aboriginal title to a particular tract of land outside a reserve exists.

In 1983, the Government of BC issued a license to Carrier Lumber Ltd. to harvest trees in the Tsilhqot’in territory.[11] The Tsilhqot’in objected by way of a blockade at Henry’s Crossing.[12] Since that time, and through changes in Chief and Council, the Tsilhqot’in have continued with their objections.

The Chief of the Xeni Gwet’in brought the first court action against this logging decision.[13]

Years later, the Chief, on behalf of the Xeni Gwet’in community and Tsilhqot’in Nations, sought a declaration of Aboriginal title and rights to part of the Tsilhqot’in Territory.[14]

The Tsilhqot’in said they have title to those lands, and trees cannot be taken unless the Tsilhqot’in grant permission.[15]

Saskatchewan Wildfire Act and Regulations (2015)

The current Wildfire Act and Wildfire Regulations in Saskatchewan were acclaimed in 2015. This Act replaced the previous Prairie and Forest Fires Act, 1982.

The main reasons for the Wildfire Act were to

-clarify responsibilities and liability for fire starts;

-allow for the collection of non-firefighting costs and damages without a civil lawsuit;

-focus on prevention and preparedness: wildfire prevention and preparedness plans required by legislation rather than by an executive director;

-regulate FireSmart practices in the wildland interface;

-clarify the responsibility for wildfire administration and suppression as it pertains to rural municipalities and industrial and commercial operators;

-reduce government administration: move from burning permits to a burn notification system;

-administer industrial and commercial operations under a results-based regulatory framework; and

-align officer authority with other environmental legislation.

According to the Wildfire Act section 27(4)(b), the Crown (Government of Saskatchewan) has a statutory responsibility to be satisfied that a resource management fire “is appropriate and not contrary to the public interest.” In approving a resource management fire burn plan, the Crown must consider the prescribed values and factors in section 11 of the Wildfire Regulations.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) Calls to Action (2015)

In June 2015, the TRC published 94 Calls to Action addressing the legacy of residential schools and advancing the process of Canadian reconciliation.

People living and working in Canada play individual and collective roles to advance the Calls to Action.

Truth and reconciliation also mean that Indigenous practices are upheld for Indigenous Peoples living and working on the land.

Prairie Resilience: A Made-in-Saskatchewan Climate Change Strategy (2017)

In 2017, the Government of Saskatchewan launched Prairie Resilience: A Made-in-Saskatchewan Climate Change Strategy.

This provincial climate change strategy focuses on the principles of readiness and resilience to support the province and its people, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prepare for changing conditions, for example, extreme weather, drought and wildfire.

Prince Albert Grand Council Wildfire Task Force Interim Report (2018)

In 2018, the Prince Albert Grand Council released their Wildfire Task Force Interim Report that advocated for “the development of a First Nations wildfire advisory council”[16] to help in overseeing wildfire operations.

Considerations included all aspects of wildfire management: location of Indigenous values, how values at risk databases are created, how to partner with Indigenous organizations and to what extent fire should be returned to Indigenous territories.

International declarations and laws

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) (2007)

UNDRIP was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in September 2007.

In May 2016, the Government of Canada announced that Canada is a full supporter, without qualification, of UNDRIP.

This declaration establishes a comprehensive international framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity, security and well-being of the Indigenous Peoples of the world. UNDRIP elaborates on existing human rights standards and fundamental freedoms as they apply to the specific situation of Indigenous Peoples.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (aka Paris Agreement on Climate Change) (2015)

Published in 2015, this document contains several excerpts relevant to Indigenous Peoples: the parties acknowledged that adaptation action should follow a country-driven, gender-responsive, participatory and fully transparent approach; should take into consideration vulnerable groups, communities and ecosystems; and should be based on and guided by the best available science, Indigenous Ecological Knowledge and local knowledge systems, with a view to integrating adaptation into relevant socio-economic and environmental policies and actions.

2015-2030 Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction is an international framework that recognizes the important roles of Indigenous Peoples in addressing disaster risk using Indigenous Ecological Knowledge and expertise on how to adapt and reduce risks from climate change and disasters.

Excerpts from the Sendai Framework acknowledge that Indigenous Peoples, through their experience and Indigenous Ecological Knowledge, provide an important contribution to the development and implementation of plans, including those for early warning.[17]

Calls for increased use of fire by land managers and fire scientists circa 2019 to present

From around 2019 to the present, there are calls for the increased use of fire in land management and natural resource management.

Scientists and land managers call for greater use of fire, including both prescribed and naturally ignited fires, to expand the “pace and scale” of restoration and promote resilience of social-ecological systems.[18]

These calls have increased as extreme wildfires are more common[19] and more disruptive to ecological and social values, including public health[20] and cultural resources.[21]

In countries such as the United States of America, national forests are revising their land management plans to expand the role of intentional fire.[22] For example, the State of California has updated its legislation to support tribal cultural burning.

However, there are significant policy obstacles, including liability concerns and air quality regulations.

International Campaign for Disaster Risk Reduction in Indigenous Communities (2022)

The 7th Session of the Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction was held in Bali, Indonesia, hosted by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. A special session was held in May 2022 in support of Indigenous disaster risk reduction.

The session focused on the following goals: understanding Indigenous-led approaches to disaster risk reduction; supporting opportunities for Indigenous Peoples’ voices to be heard and recognized at local, regional, national and international levels about their lived experiences and needs in disaster risk reduction; and harmonizing Indigenous experiences in disaster risk reduction (making further connections with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction).

[1]Kimmerer R. W., & Lake, F. K. (2001). The role of Indigenous burning in land management. Journal of Forestry, 99(11), p. 36.

[2]1895 Police report and Sessional Paper No. 28 of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police 1910.

[3]B. Highway, personal communication, November 30, 2022.

[4]Quiring, D. M. (2014). CCF colonialism in Northern Saskatchewan: Battling parish priests, bootleggers, and fur sharks. UBC Press, p. 170.

[5]Mandell Pinder LLP Barristers & Solicitors (n.d.). https://www.mandellpinder.com/landmark-cases/

[6]Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. (2019). Indigenous rights, title and the duty to consult. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/aboriginal-rights-title-and-the-duty-to-consult-a-primer

[7R. v. Sparrow, [1990] 1 SCR 1075, 1990 CanLII (SCC). http://canlii.ca/t/1fsvj.

[8]Ibid.

[9]Ibid.

[10]Ibid.

[11]Ibid.

[12]Ibid.

[13]Ibid.

[14]Ibid.

[15]Ibid.

[16]2018 Wildfire Task Force Interim Report: https://www.pagc.sk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/PAGC-Wildfire-Task-Force-Interim-Report-Apr-2018.pdf, p. 2.

[17]https://www.unisdr.org/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf

[18]Kolden, C. A. (2019). We’re not doing enough prescribed fire in the western United States to mitigate wildfire risk. Fire, 2(2), 30; McWethy, D. B. et al. (2019). Rethinking resilience to wildfire. Nature Sustainability, 2. 797–804; Spies, T. A. et al. (2019). Twenty-five years of the northwest forest plan: What have we learned? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 17. 511–552.

[19]Miller, J. D., & Safford H. (2012). Trends in wildfire severity: 1984 to 2010 in the Sierra Nevada, Modoc Plateau, and southern Cascades, California, USA. Fire Ecology, 8. 41–57; Reilly, M. J. et al. (2017). Contemporary patterns of fire extent and severity in forests of the Pacific Northwest, USA (1985–2010). Ecosphere, 8(3). 1–28.

[20]O’Dell, K. et al. (2019). Contribution of wildland-fire smoke to US PM2.5 and its influence on recent trends. Environmental Science & Technology, 53(4). 1797–1804. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b05430

[21]Welch, R. (2012). Effects of fire on intangible cultural resources: Moving toward a landscape approach. In K. C. Ryan, A. T. Jones, C. L. Koerner, & K. M. Lee (Eds.), Wildland fire in ecosystems: Effects of fire on cultural resources and archaeology (pp. 157–170). USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, General Technical Report RMRSGTR-42.

[22]Spies, T. A., et al. (2019). Twenty-five years of the northwest forest plan: What have we learned? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 17. 511–552.